Why you can’t blame Obamacare for the crisis in ‘underinsurance’

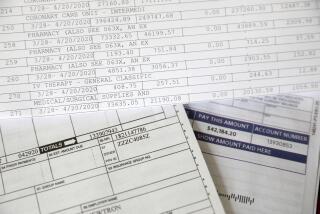

The focus of the healthcare debate has shifted abruptly from helping the uninsured to helping the “underinsured” -- those people who have insurance but still face high co-pays and deductibles.

Thanks to a couple of timely surveys of medical consumers, the focus of the healthcare debate has shifted abruptly from helping the uninsured to how to help the “underinsured.” These are the people who have insurance but still face co-pays and deductibles that could break them financially if they had a major medical need.

It shouldn’t surprise anyone that anti-Obamacare conservatives have seized on the trend, declaring it another flaw in the Affordable Care Act and blaming the act for making it worse. They’re wrong, and their own figures prove it. More on that in a moment.

The Commonwealth Fund produced the most thorough look at the issue last week with a report placing the ranks of the underinsured at 23% of all those 19 to 64 years old who were insured all year. The figure hasn’t statistically changed since 2010, but it’s sharply higher than 2003, when the fund first examined the measurement.

Commonwealth defines “underinsured” as having out-of-pocket costs, not counting premiums, that are 10% or more of household income (5% or more for those earning less than 200% of the federal poverty level -- $47,100 for a family of four) or having a deductible that is 5% or more of income.

Many healthcare experts, whether conservative or liberal, like deductibles because they can discourage unnecessary treatments; the argument is that consumers with “skin in the game” will be more discerning about whether to see a doctor for a minor scrape. When deductibles get too high, however, they tend to discourage necessary as well as unnecessary treatments. Some deductibles in the individual market, even among plans compliant with the Affordable Care Act, have reached that point.

The trend is even leaching into the employer-sponsored insurance market. There, deductibles have been (and remain) much lower than in the individual market, but they’re rising: the Kaiser Family Foundation says the percentage of workers in employer plans with deductibles higher than $1,000 for single coverage rose to 41% last year from 10% in 2006.

Conservatives have noticed the trend, and naturally they blame the Affordable Care Act: “Obamacare advocates seek to fix problem they made worse,” is the headline on Byron York’s Washington Examiner piece Monday. (He’s seconded by Mickey Kaus.) York cites statistics placing “mid-range deductibles” at $1,200 for single coverage and $2,400 for a family plan. “How did those deductibles get so high in the first place?” he asks. “The answer is Obamacare.”

Is that so? Let’s take a look.

York asserts that the Affordable Care Act, by outlawing lifetime caps on healthcare benefits and the denial of coverage to those with preexisting conditions, and by mandating that children be covered on their parents’ employer plans up to age 26, left insurers with little choice but to jack up deductibles to remain profitable.

None of this holds water. For a start, the trend of rising deductibles pre-dated the Affordable Care Act by years. York even acknowledges this; he cites Commonwealth Fund figures showing that the percentage of adults with deductibles equal to 5% of household income rose from 3% in 2003 and 2005 to 6% in 2010. The figure reached 11% last year.

York and Kaus are correct in noting that the percentage of people facing high deductibles relative to income accelerated following the ACA’s passage, if modestly. What they don’t acknowledge is that the trend was accelerating before the ACA, too. Most of that is the handiwork of employers, who provide most Americans with their health insurance. Employer-sponsored insurance already tended to incorporate most of the mandates imposed by the ACA even before the law’s passage; plainly, factors other than the ACA have been at work in that market, including the desire of businesses to cut back on wages and benefits generally.

What about the individual market, the focus of the ACA? Here’s the Commonwealth Fund’s chart of the trends in deducibles. You’ll notice that in the individual market, while the percentage of adults with deductibles higher than 5% of income did rise through 2012--another trend that had started well before the ACA--since then it has come down, from 30% of those with individual coverage in 2012 to 24% in 2014. Neither York nor Kaus mentions this.

The ban on exclusions for preexisting conditions, moreover, only went into effect in 2014 -- and it was paired with the individual mandate, which required everyone to buy coverage. How a provision that didn’t exist until 2010 and didn’t become effective until 2014 could produce a trend dating back at least to 2003, York doesn’t say.

York glosses over another point that goes to the essence of the Affordable Care Act: Before 2014, deductibles were utterly irrelevant to millions of Americans. That’s because exclusions for preexisting conditions kept them from buying any insurance at all.

York writes: “If a couple had a deductible of, say, $500 in the past, and it’s now $3,000, that couple has to spend a lot of money out-of-pocket before reaping the benefits of coverage.”

One reason deductibles were relatively lower in the past was precisely because insurance companies could cherry-pick the healthiest customers. Insurers steering clear of older customers or those with a history of chronic disease, not to mention cancer or worse, could offer low deductibles to customers with low likelihood of claims, and still pretend you’re in the insurance business. The Affordable Care Act ended that business model, and good riddance.

Critics of high deductibles seldom mention that for many people, the Affordable Care Act offers a built-in remedy: cost-sharing is subsidized for those earning 250% of the poverty level or less, and heavily subsidized for those at 200% or below; the subsidies are in addition to the premium assistance provided to those earning up to 400% of the poverty level.

Indeed, while York and Kaus assert that since the Affordable Care Act, the problem of underinsurance has picked up steam, the truth is exactly the opposite because of the cost-sharing subsidy: underinsurance has begun to ebb for lower-income people -- for those earning less than 200% of the federal poverty level, it has fallen to 42% in 2014 from a peak of 49% in 2010.

Nor do critics mention -- York certainly doesn’t -- that the Affordable Care Act also mandates that many benefits be provided outside the deductible, including preventive screening and immunizations.

But, yes, high deductibles are a problem that should be solved. It would be good to hear conservatives propose a solution, short of repealing Obamacare and returning to the golden years of insurance you couldn’t buy at all.

Keep up to date with the Economy Hub. Follow @hiltzikm on Twitter, see our Facebook page, or email mhiltzik@latimes.com.