Changing of guard among L.A. County supervisors not happening quietly

The final weeks of elected officials’ terms are typically spent packing up boxes, exchanging goodbyes, and handing out proclamations to constituents and loyal staff members.

But facing a historic changing of the guard, the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors has been making moves designed to solidify what members view as a legacy of fiscal responsibility, and some believe, box in their successors on key personnel and labor decisions.

This year’s vote for two new supervisors is seen as the most pivotal in decades, in part because it probably will determine if the balance of power on the five-member elected panel tilts more toward organized labor or business and development.

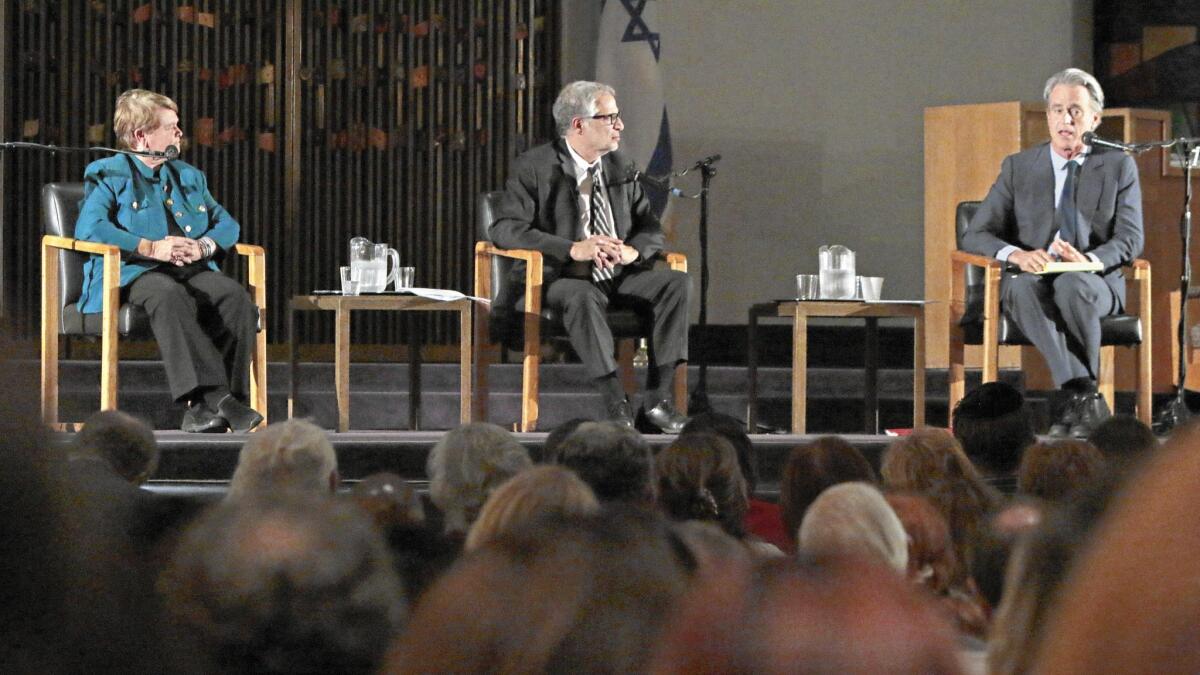

Though members are officially nonpartisan, two Republicans, Don Knabe and Michael D. Antonovich, have frequently allied with Democrats Zev Yaroslavsky or Gloria Molina on key budget and labor negotiation issues.

Molina is being replaced by former Obama administration labor secretary Hilda Solis, who won election in June with strong union backing. Supervisor Mark Ridley-Thomas, who is not up for election, joined the board in 2008 with the help of millions of dollars in union spending.

The board will be rounded out Tuesday when one of two Democrats, Sheila Kuehl or Bobby Shriver, is chosen by voters to replace Yaroslavsky. That hard-fought contest has seen union-affiliated campaign money flow toward Kuehl, and Shriver’s bid attract lopsided support from investment, development and real estate interests. The winner of that race and Solis will take office in December.

With its time running out, the board recently voted to require a four-fifths supermajority approval for any future employee salary and benefit increases. The board also increased management’s influence over the county Employee Relations Commission, which decides potentially costly workplace disputes affecting thousands of workers.

But the biggest battles have been over personnel. In recent weeks, and over the objections of Ridley-Thomas, board members have pressed ahead with key executive appointments, including naming new county counsel, the board’s top legal advisor, and an auditor-controller. The board also has pushed forward with a search for a chief executive.

Ridley-Thomas said those decisions and other pending selections of top managers for the child welfare system and public health programs — including efforts to respond to the Ebola threat — should be left to the incoming, reconstituted board.

“It seems to me that it would be appropriate for professional courtesy to be extended to the new members,” he said. “Why should this board determine how the other board functions?”

Board members also have spent months circling a more significant personnel decision — choosing a replacement for retiring county chief executive officer William T Fujioka. Fujioka and his staff of 500 supervise the heads of most county agencies, negotiate labor agreements, draft most major recommendations considered by the board and prepare a $26-billion-a-year budget.

An executive search firm is recruiting candidates, and Fujioka is scheduled to depart just days before the newly elected board members are seated in December.

Knabe initially argued in a recent Times interview that the board should move quickly to select a chief executive so it can take advantage of current members’ long years of experience.

“I don’t think we can afford to wait around,” he said. “You’re losing a lot of institutional knowledge with the loss of Zev and Gloria.”

Termed-out supervisors Molina and Yaroslavsky also suggested, at least at first, that they might consider naming a chief executive before they leave office. But in recent days, amid push-back from Solis and Shriver, in particular, current supervisors said they would leave the decision to the new board. Molina said she was persuaded to hold off by Solis, whom she endorsed during the spring campaign.

“The direction and many of our ideas and positions may be very different,” Solis said of the chief executive selection process. “I don’t know what the hurry is.”

In a second interview, Knabe acknowledged that the board had backed off. The incoming board members are “going to have to live with that decision,” he said, “so there was consensus on the board that they’re going to be part of the decision-making process.”

No official “short list” of chief executive candidates has been prepared, but the names of potential contenders circulating at the Hall of Administration have included Los Angeles city Chief Administrative Officer Miguel Santana, county Deputy Chief Executive Officer Santos Kreimann and county Probation Department Chief Jerry Powers.

Some critics say members have angled in other ways to limit the next board’s options, particularly on labor issues.

County labor groups, which opposed current members choosing Fujioka’s successor, have attacked the new policies affecting pay and benefits increases and how members of the Employee Relations Commission are appointed.

Bob Schoonover, president of Service Employees International Union Local 721, which represents more than 50,000 county workers, said that imposing a supermajority requirement on decisions involving employee compensation is an example of “extreme inefficiency.” He stressed that the incoming board can overturn the rule with a 3-2 vote.

Blaine Meek, chairman of the Coalition of County Unions, said with Tuesday’s election, “L.A. County voters have the opportunity to determine the future of our region.”

“The newly elected leaders should be able to make policy decisions and appoint a new chief executive officer that reflects the vision articulated to voters,” he said.

One simmering issue with potentially far-reaching consequences for how agencies are managed centers on the authority of the next chief executive.

As part of a 2007 reorganization intended to clarify accountability, the chief executive was given more direct oversight of three dozen departments that provide services ranging from social assistance and beach safety to welfare programs and restaurant inspections.

The change followed a series of scandals over patients’ deaths and mismanagement at the county’s King/Drew Medical Center, as well as alleged abuse of wards in the county’s juvenile lockups. But revamping the organizational chart failed to eliminate high-profile scandals, such as minors involved in the child welfare system being abused and killed. Supervisors have taken back direct control of two departments as a result.

Now, Ridley-Thomas and Antonovich want to further scale back the powers Fujioka had.

The current system has created “bureaucratic distance” that makes it difficult for supervisors to effectively assess the performance of department heads, Antonovich said. Ridley-Thomas — who has a tense relationship with Fujioka — said too much power has been vested in the chief executive’s office.

Both supervisors want to return to the previous system, under which department heads reported to the elected board.

Yaroslavsky said the current board never fully embraced the stronger chief executive model, and found ways to continue meddling in agencies’ day-to-day business. That has made it difficult for the county to attract top talent to management positions, he said.

For many, the last search for a new county chief executive was emblematic of the recruiting challenges the board has faced.

After a six-month, nationwide search, one top candidate turned down the job. Another accepted and then changed his mind the next day. It was another six months before Fujioka, then Los Angeles City Hall’s top administrator, agreed to take the job, after initially rejecting it.

“I know there are good people who wouldn’t touch this job with a 10-foot pole,” Yaroslavsky said. “They don’t like the culture and the micromanaging that is attendant to this organization.”

But Sandy Vargas, a former county administrator in Minnesota who turned down the Los Angeles job in 2007, said the stature and complexities of the county chief executive job are both appealing and “daunting.”

“The bigger the county, the bigger the budget, the bigger some of the problems can be,” Vargas said.

Ridley-Thomas hopes that one of the incoming board members will provide the needed third vote to put supervisors back in charge of various department managers. Kuehl and Shriver have said the chief executive should retain greater independence and direct oversight of department heads.

Solis said she was willing to consider having board members directly supervise agency managers.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.