Since Obamacare, rate of growth in L.A. County ER visits slows

The pace of growth in Los Angeles County emergency room visits slowed in the early months of Obamacare, according to state records that offer a first local look at a key objective of the healthcare overhaul.

During the first three months of expanded health insurance coverage required by the federal Affordable Care Act, emergency room visits by patients who didn’t require hospitalization increased 1.7% in the county compared with the same period last year, a Los Angeles Times analysis of data from 75 hospitals shows. Annual ER visits in the county had increased 3% last year and 5% in 2011 and 2012.

------------

FOR THE RECORD:

A shareline on an earlier version of this article incorrectly said fewer patients are visiting public hospital emergency rooms since Obamacare. It is the number of ER visits that is down at L.A. County public hospitals.

------------

The preliminary data contrasts with the findings of a recent, often-cited study that showed a dramatic increase in emergency room usage when insurance coverage was expanded for poor patients in Oregon.

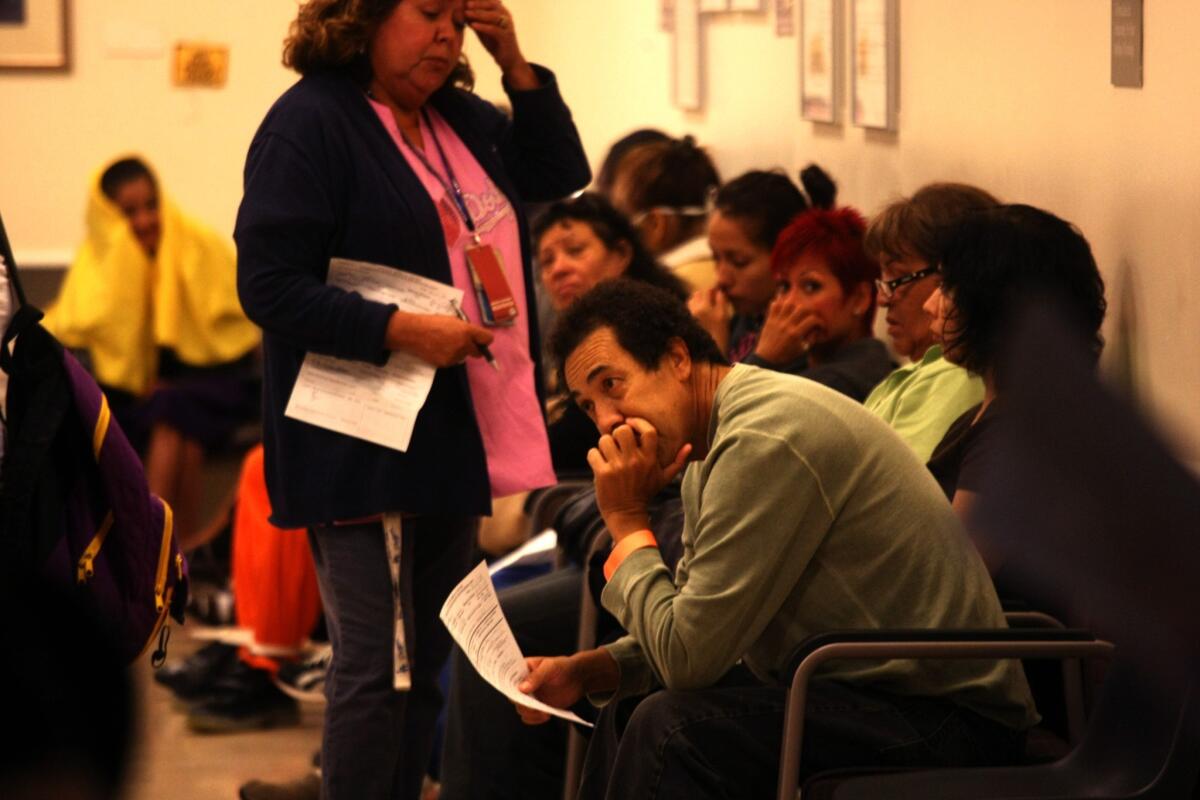

The Times analysis highlights shifting patterns of emergency room use and the challenges hospitals could face as they adapt to the new healthcare environment. Notably, thousands of new patients headed to private hospital ERs, while public hospitals that traditionally serve uninsured, poorer patients saw a dip in emergency room visits.

The inefficiency of using crowded and high-cost emergency rooms for basic medical care is a central problem Obamacare is supposed to correct. By requiring most Americans to sign up for medical insurance — and subsidizing premiums for the needy — the new healthcare system is intended to improve regular, preventative care and reduce unnecessary emergency room usage.

As a result, ER data is being closely watched by those seeking “to declare success or failure” for the controversial healthcare law, said Sabrina Corlette, a professor at the Georgetown University Health Policy Institute’s Center on Health Insurance Reforms. She said an initial increase of just 1.7% in the nation’s most populous county is a “great sign.” But gathering enough data to gauge the lasting effect of Obamacare on ER use is still “going to be years away,” she said.

Long-term studies several years after a health insurance expansion in Massachusetts found ER visits had declined or were unchanged. But in Oregon, one recent 18-month study found newly insured patients receiving Medicaid, the government program for the poor and elderly, went to the emergency room 40% more than people without coverage.

Some experts believe such initial spikes are caused by a rush of newly covered patients who postponed needed care due to cost or other barriers. Critics of Obamacare warn hospitals and doctors will be overwhelmed with newly insured patients — especially those with lower cost, government-subsidized plans — and promised savings will never materialize.

Both sides are monitoring early reports on ER visits, but agree they may present only a partial picture of the healthcare law’s effects. Many people didn’t sign up for Obamacare coverage until late March or early April, some experts note, and thousands of applicants for Medi-Cal, the state’s version of Medicaid, remain mired in a paperwork backlog.

What is clear is that California’s percentage of uninsured people has dropped sharply over the last year, cut in half to 11%, a recent survey found. Millions of previously uninsured Californians have signed up for coverage and are using it.

In the first three months of this year, most privately-run hospitals in Los Angeles County saw increases in emergency room visits, pushing their numbers above the countywide average, state data shows.

Long Beach Memorial Medical Center posted one of the biggest jumps, with visits up 16% from a year ago to 285 patients per day, said Tamra Kaplan, the hospital’s chief operating officer.

Patients covered by Medi-Cal, which was expanded under Obamacare, accounted for most of the increase, and the hospital’s share of uninsured patients dipped slightly, she said.

The same trend played out across Los Angeles County in the first three months of 2014, according to data collected by the state. The proportion of emergency room patients covered by Medi-Cal grew from 32% in the first quarter of 2013 to 38% this year. The number of emergency room patients without coverage and responsible for their own medical bills dropped from 18% to 16%.

“For us, self-pay means there’s no pay,” Kaplan said. “So from a financial perspective, it actually looks as little bit better than it did a year ago.”

Dr. Jay Lee, a primary care physician whose office is across the street from Long Beach Memorial, said he is seeing more newly insured patients referred to him from the emergency room. Several show up with long lists of medical ailments — sometimes numbering into the teens — that they’ve been waiting months, or even years, to discuss with a doctor, he said.

“It can be a little overwhelming,” Lee said, describing patients who begin crying with relief as they work through their medical concerns. Many say they’ve never received care outside of an emergency room.

On a recent Sunday afternoon in downtown Los Angeles, Medi-Cal patient Omar Diaz, 31, arrived at California Hospital Medical Center’s emergency room complaining of persistent stomach pain.

He’d been at the hospital’s ER three months earlier for the same problem, he said.

“I don’t usually need to go to the doctor,” Diaz said, who lives nearby. “So I just come here when I do.”

Emergency room visits at the hospital rose 8% in the first half of the year, officials said. One in five ER patients doesn’t need emergency care, said Bob Quarfoot, the hospital’s vice president of business development. The hospital is hoping the share of unnecessary visits will decline as newly insured patients find primary care doctors, he said.

But experts say altering past patterns of healthcare use could be slow and difficult, partly because emergency rooms can be convenient for those who don’t feel they can wait for scheduled office appointments. Indeed, some patients seek emergency care on the advice of their doctors, who want them to receive faster attention, said Sara Rosenbaum, a health researcher at George Washington University.

“People go to the emergency department because they don’t have choices,” Rosenbaum said.

Los Angeles County health officials attribute the decline in emergency room visits at their public hospitals to getting Medi-Cal patients connected with primary care doctors.

First quarter emergency room visits not requiring hospitalization at Los Angeles County-USC Medical Center, Olive View-UCLA Medical Center and Harbor-UCLA Medical Center had increased for six consecutive years through 2013. This year, state data show an 8% decrease in visits between January and March.

Dr. Christina Ghaly, deputy director of strategic planning for the county’s Department of Health Services, said county hospitals are benefiting, like other institutions, from an uptick in insured patients and less uncompensated care. Also, fewer patients could help relieve long-standing problems with overcrowding and lengthy waits at emergency rooms at the public hospitals.

Part of the decrease in ER use is being attributed to a county effort begun three years ago to transition into Obamacare. People who were going to be eligible for Medi-Cal in 2014 were enrolled in a county-run health program and could visit county clinics and doctors. Those patients aren’t rushing to the emergency room now, Ghaly said.

However, Dr. Dylan Roby, a health policy professor at UCLA, said there’s added financial risk for the county because those new Medi-Cal patients are no longer tethered to the public, county health care system. They’re likely to explore the care available from other doctors and hospitals, he said.

If too many patients leave the county system, Roby said the big public hospitals could be left with only those who can’t pay.

“That could spell problems,” he said.

soumya.karlamangla@latimes.com

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.