Challenges at school for migrants: Overcoming trauma, learning English

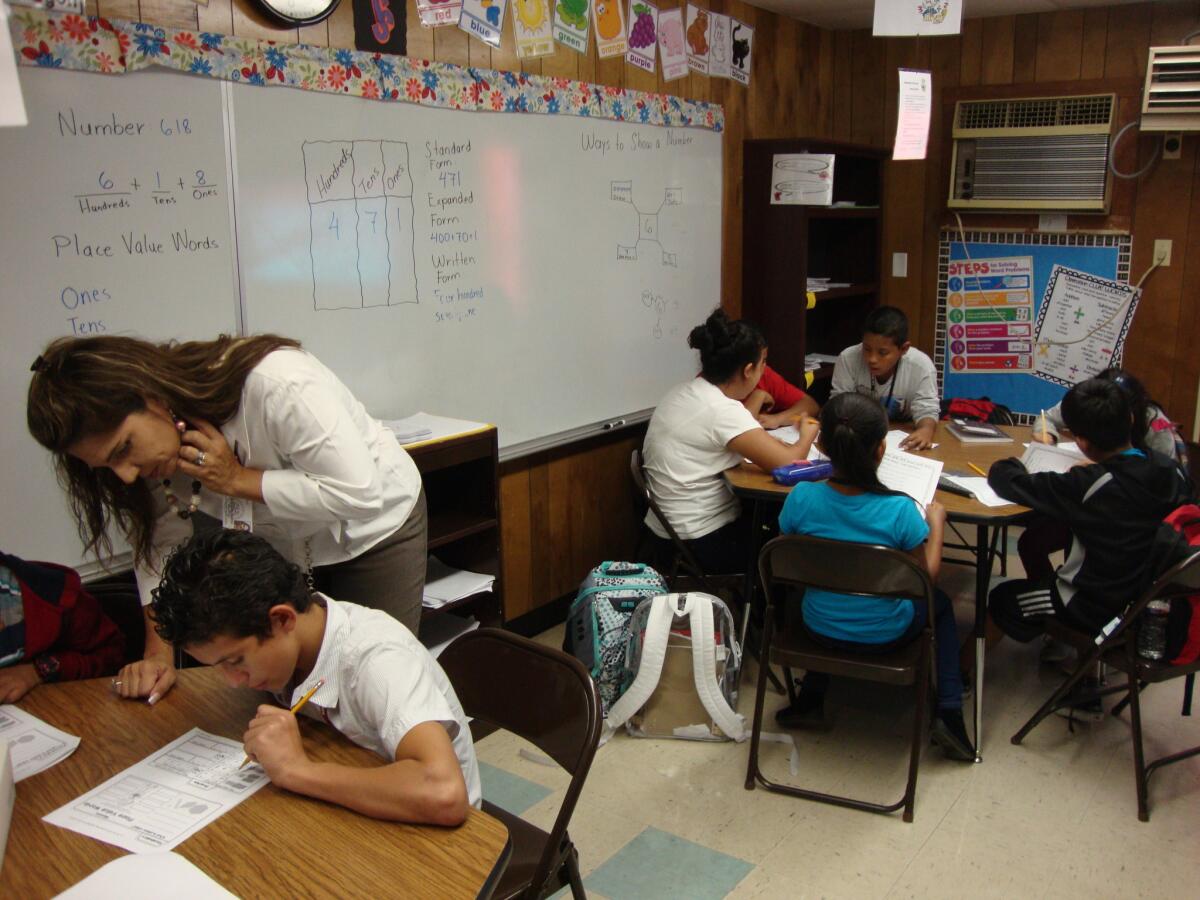

Principal Marie Moreno works with Central American immigrant students at Las Americas Newcomer School in Houston last year.

Thousands of young immigrants, many of them making the dangerous journey alone, entered the United States illegally last year — a surge of migration that has created special challenges for the youths, their parents and the schools trying to serve them.

Those challenges are on display every day at Las Americas Newcomer School, which enrolls immigrant and refugee students, grades 4 through 8, in Houston’s low-income Gulfton neighborhood. The immigration surge meant 316 additional students for Las Americas, about 260 of them from Central America.

For Principal Marie Moreno, it means dealing with students who suffered violence, are sometimes unschooled even in their native tongues, and are still adjusting to life without parents who left them behind years ago to work in the United States. The Times chronicled those challenges and met with Moreno six months ago.

More than 68,000 unaccompanied children entered via the U.S.-Mexico border illegally in the last fiscal year. More than 53,500 of them were placed with parents and other sponsors in the U.S.

Texas had the largest number of children placed with sponsors — 7,408 — and more than half ended up in the county surrounding Houston.

The Times recently caught up with Moreno just as she finished explaining to a newly arrived Salvadoran student’s mother that, despite what her daughter says, the girl has daily homework. Moreno talked about the daunting challenges the students and their teachers continue to face:

What do you hear from other teachers in Texas about how they are working with these students, the challenges they face?

Teachers are really struggling. It’s a lot of the language — they just need more support in language. Behavior is another one. The social worker [at her school] goes to a lot of meetings with people from other schools. She came to me and said, “I kind of feel better. Everyone is struggling; it’s not just us.”

When we last talked, you had a counselor and a new social worker at the school. How has that worked out?

That social worker was a godsend from heaven. Most of our kids have faced some kind of trauma. Of the 316, about 65 of them are getting some kind of treatment right now, and if we can get more help, we’ll add more.

How are the students faring at school academically? Socially? Have they had trouble adjusting?

I’m no social worker, but some of these kids really just need someone to talk to. This is not what they had imagined. Mom is not the mom they remember. They get rebellious and say, “She just brought me here to watch the other kids.”

There was this boy, one of my students — someone in El Salvador sent him a photo of his dad on Facebook moments after he was killed. You could see him on the floor where they shot him in the head. I said, “Who sent this to you?” He says, “It was my cousin.” He’s 13.

Why would his cousin send him that?

I guess to tell him it had happened.

So what did you do?

We’re monitoring him. The social worker talks to him.

What about the other students?

It’s exhausting because the way we do school in America is different than the way they do school over there. I realize that I have to do a lot more teaching of teachers. What I’ve been trying to do is to show [the teachers] videos to understand where [the students] come from so that they can basically understand what it took for these kids to get through.

I’m not looking for sympathy. I’m looking for understanding. Sympathy doesn’t get these kids anywhere, the “Poor baby, you can’t get this so I’ll give you the answers.” That’s not going to help. They have the drive, but the only way out is education. They need to learn how to live.

Do students talk about why they came? What it was like?

Some of them have, some of them haven’t. My social worker does group therapy because she says their stories are similar enough that they can sort of grieve together and she can pair them up to share their stories.

They draw pictures. She has clay back there and you can see them play with it and then pound, pound, pound! They’re sort of reliving it. And she’s able to get more out of them. That provides them an escape.

What do the students draw?

Sometimes it could be just their home country, what they miss. If the social worker knows there’s three kids in the family and they draw other kids in there, she’ll ask and they’ll say, “Oh, this is my brother back in El Salvador.” So she’s able to draw them out. If there’s something she can help them do on campus, like an old routine, she’ll let them do that. A lot of kids worked for a living over there — they had to cut corn or help Grandmother sell the corn — so maybe give them a task.

They’re very pleasing kids. They want to please you, to help support. Back home if they went to school, they didn’t go all day. Now, their parents say, “Your job is just to go to school.” They don’t think going to school and doing homework is being responsible enough.

How are the new Central American students doing academically?

They’re low-proficiency. We have some kids — we gave them a Spanish book and they couldn’t even read it. They were illiterate in their first language, which makes it difficult to learn a second language. Today, six months later, they’re able to read at about a second-grade level in English. They’re doing really well.

What they struggle with — they can read words, sound them out — but it’s comprehension. They’re able to say, “The boy was going to the store.” We’re trying to get them to understand, “OK, what was he doing there?”

So I’m asking if I can keep them another year. Because they’re supposed to only be here a year before they go next door [to English as a second language classes at Jane Long Middle School]. But if they’re not reading on grade level, they’re going to really struggle next door. So I’m asking [the district], but I won’t hear back until May.

You’re facing standardized state tests later this month. How prepared are your students?

One of the kids asked me, “When are we going to get the test booklet with the questions? Because in El Salvador, they gave it to us and we memorized it.” I told him, “This is a practice test, don’t bother memorizing it — the test I’m going to give you will be different.”

Then he said, “Well, can I have it the day before?”

He just couldn’t understand the concept of mastery, of learning the content. He’s 13 years old.

How about the Central American students’ behavior in school? Has that changed?

I had a kid whose behavior went from really, really good to really, really bad. I had the social worker get on that and we found out he was days from being deported.

Was that one of the students you told me about last time — the one who transformed?

Yes, the 14-year-old from Honduras. So that was his way of acting out.

The rest are awaiting the outcome of their immigration court cases?

Yes. I only know one who got to stay so far with papers. They hate to go to court, because they’re really afraid of being deported.

So was the Honduran student deported?

No. The good thing was, that was sort of put off. So he’s good again.

Mom works nights. He’s just getting in with the wrong crowd. So I put him at that desk all last week. [She pointed across her office to a small desk.] And I put that there, too. [She pointed to a sticky note with a drawing of an eye and the words “I am watching you work!” in Spanish.]

I gave him a workbook. He said, “I don’t know these words!” So I gave him a dictionary and said, “Look them up.” I made him suffer. I pleaded with him. He says, “I’m going to behave, I promise.”

Every day is a new day. I went to his house once. I probably need to go again.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

On Twitter follow @mollyhf for news from Texas and across the nation.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.