Q&A: Leading scientist warns that Ebola eradication may be elusive

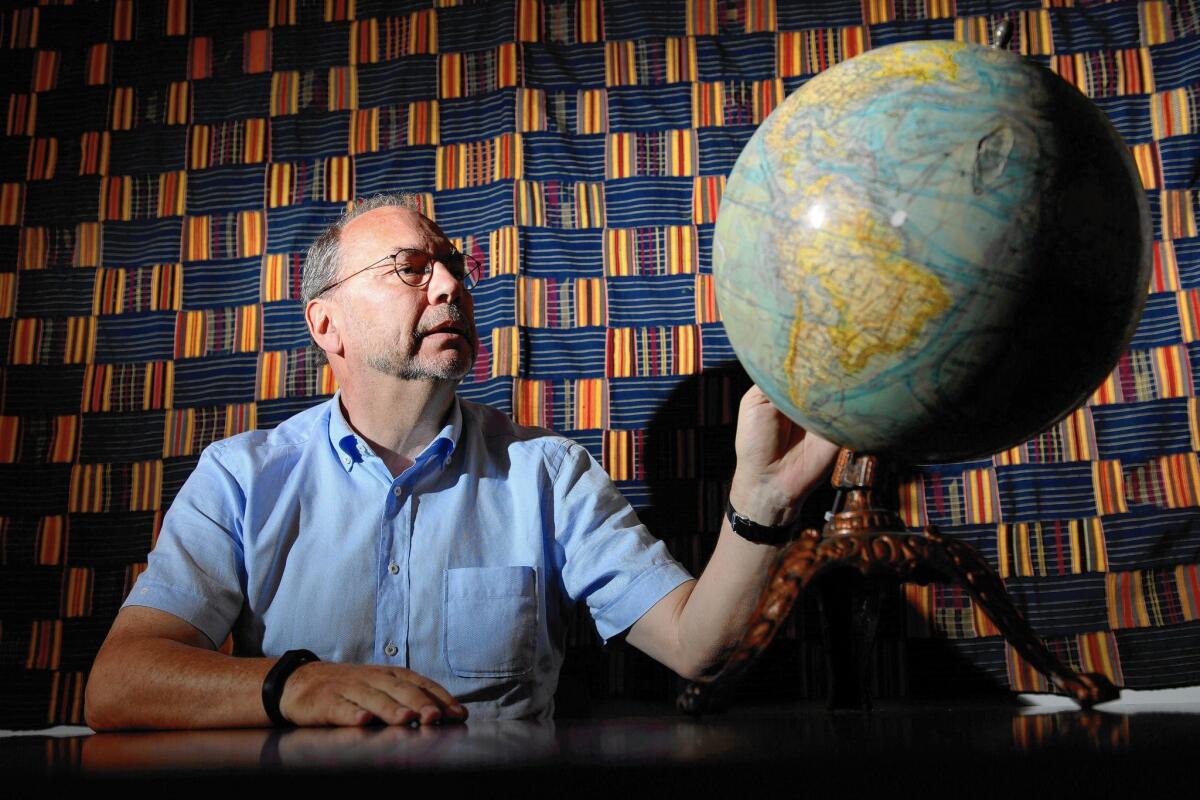

Nearly 40 years ago, Dr. Peter Piot was on a team of scientists in the Belgian city of Antwerp that discovered the Ebola virus.

An airline pilot had delivered a blood sample from a Belgian nun who had fallen mysteriously ill in the central African country then known as Zaire. The team worked in gear unimaginable today, just white lab coats and gloves. None of the members got sick, and Piot became one of the world’s leading experts on Ebola. He is now director of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine and an outspoken critic of the slow international response to the Ebola epidemic in West Africa.

The World Health Organization estimates the virus has infected more than 21,700 people and killed about 8,600 of them. While some health officials are predicting the epidemic in Sierra Leone, Guinea and Liberia can be contained by the end of the year, Piot wonders whether the methods that have worked in the past — isolating the victims, tracing their contacts and monitoring them for symptoms — will defeat an outbreak of this scale.

He recently joined the Paul G. Allen Family Foundation as an advisor to its $100-million effort to eradicate Ebola. He spoke to The Times during a recent trip to Seattle. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

You were in Sierra Leone before Christmas. What was the situation there?

Everybody told me the response is getting much better. I think in terms of treatment centers and all that, that’s now probably covering the needs. And it’s much better organized than before.

But I think that the biggest challenge is going to be, now that the number of cases is starting to come down, people say it’s done. But the epidemic goes up and down. It moves from there to there.

Guinea has had Ebola for over a year, but the first announcements about the epidemic were just 10 months ago, and the WHO didn’t declare it an international public health emergency until August. Why did it take so long?

Ebola had never hit West Africa, so it was the unknown. There was denial, definitely, from the local authorities. The international community didn’t react also.

Why was the WHO slow to react?

Their capacity to respond to epidemics was cut enormously [because of] budget cuts. And they’re very decentralized. The one regional office in Africa is not very competent; they have not done their job. In Geneva they have a good team, but it was reduced due to budget cuts. I think there was a collective underestimation of the situation.

Were there problems beyond WHO?

I think the fact that the infrastructure and the health services in these countries are so under-resourced and have few doctors, nurses and all that. Because of civil war, most professionals left the country. Liberia had 51 registered doctors in 2010 for the whole country. What do you do? Where do you start?

There have been other Ebola outbreaks that were contained quickly. Were they mostly in rural areas, and doesn’t that make a big difference in fighting the disease?

Yes, except for one in a town called Kikwit and one in Isiro [in Zaire, known today as the Democratic Republic of Congo]. But even then, it’s like 200,000 to 300,000 people. And in Congo, mobility is difficult, so that’s an issue. In West Africa, the roads are not bad.

So that helps keep the virus contained?

Yes, but also the rapid response. Once you let it get out of control, it’s far more difficult to contain. What keeps me busy at the moment — besides making sure that the effort continues, that we don’t think it’s over — is how are we going to know that it is over, that there is no case left in these three countries?

Is it possible to eradicate it completely?

We have no choice, and it has been done before. The difference is in DRC they could eradicate that particular outbreak that’s in one location. Now you have to do that in, I don’t know, 1,000 locations in three countries. And each [response] has to be perfect.

A big challenge is sustaining that effort in the minds of people. I’m not only thinking about financially, with all the resources and the treatment centers, but in people’s minds. That’s going to be quite a challenge, [ensuring] that they don’t return to traditional burial practices, for example, which include saying farewell to your loved ones, hugging, touching, having a meal in the presence of the dead body. When you think of it, it’s quite a moving way of saying goodbye to a loved one.

What is the biggest need for innovation in dealing with this outbreak?

Good question. One of the reasons I am an advisor to the foundation here is because I think this is quite a source of innovation. For classic innovation, we need treatments and vaccines. But also we have social innovation, and that is how to have safe and dignified burials, changing the rituals. And then thirdly, I think it’s about data, about communication.

Do the traditional means of fighting the disease work on such a large scale?

That remains to be seen. It definitely works for smaller outbreaks. But I think they may not be sufficient when entire nations are involved. You have to be perfect in 1,000 places to contain it. Is that possible? So it could be that we need a vaccine to really get rid of [the virus].

Can it be totally eradicated? I don’t think so, because there’s a virus reservoir out there, probably a bat. We’re not going to kill all the fruit bats. So in other words, we need to be prepared for the next outbreak by having early warning systems, hopefully have a vaccine and a treatment, and [have them] stockpiled where the reservoir is.

Are we anywhere near developing a faster diagnostic tool or a vaccine?

I think we have a realistic chance that there will be an effective vaccine. Trials have started. But earlier diagnostics, not yet. What would be fantastic is to have an early diagnostic tool that can tell me, one day after being infected, that infection is detected. That, I think, is an urgent research priority.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.