Editorial: Iran’s trial of Washington Post writer: Secrecy, not justice

This September 10, 2013 photo shows the Washington Post Iranian-American journalist Jason Rezaian and his Iranian wife Yeganeh Salehi during a press conference in Tehran.

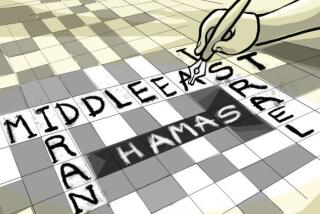

A Revolutionary Court judge in Tehran held a two-hour hearing Tuesday in the espionage trial of Washington Post correspondent Jason Rezaian, who was born and raised in the Bay Area and holds dual U.S. and Iranian citizenship. Because the court proceedings are secret and the indictment remains under wraps, little is known about the specific charges against Rezaian, and virtually nothing about what evidence Iranian investigators think they can present to prove that he committed a crime. This is not a justice system but the machinery of oppression, and the international outcry over Iran’s actions against Rezaian is fully justified.

Sadly, Rezaian isn’t the only American to have faced charges in Iran’s Revolutionary Courts, which are closely tied to the government’s security apparatus and are often used to squelch dissent, including by sentencing political protesters to death. Amir Hekmati, a decorated U.S. Marine veteran from Flint, Mich., is currently serving a 10-year sentence for “cooperating with hostile governments” after being arrested while visiting relatives in 2011. Christian pastor Saeed Abedini of Boise, Idaho, was sentenced in 2013 to eight years in prison after being convicted of establishing churches in private homes. Both cases were heard in secret, and in Hekmati’s case, without the defendant or his lawyer being present.

Each nation has the right to adopt and enforce its own laws, preferably in keeping with international standards of justice and due process. But Iran’s Revolutionary Courts fall far short of any objective standard of fairness. While we take a professional interest in the right of the world’s journalists to work without undue interference, we take a human interest in the right of all people not to be deprived of liberty through secret proceedings, hazy evidence and a rigged process.

Rezaian and his wife, Iranian photojournalist Yeganeh Salehi, were arrested in July. Salehi was later released on bail, but Rezaian has been held, at times in solitary confinement, in Tehran’s Evin Prison. He has met only twice with his lawyer, once in an introductory session in a judge’s chambers and again in a 90-minute session in April in the presence of an official interpreter. Afterward, the lawyer, Leila Ahsan, said the charges included espionage, “collaborating with hostile governments,” “propaganda against the establishment” and collecting details about Iranian policies and passing them to “individuals with hostile intent.”

If those charges can be backed up, then Iran owes it to the international community to prosecute openly and fairly. That it chooses not to do so suggests the goal is political, not judicial, and the entire process deserves the international condemnation it has received.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion and Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.