Great Read: At Bela and Martha Karolyi’s retreat, gymnastics charges ahead

Afternoon descends on the piney woods of East Texas with a heat that clings to your skin, the air so thick you have to work at drawing a full breath.

Not that the owner of the Karolyi Ranch seems to mind as he bounces along in a utility vehicle that looks like a supercharged golf cart, its knobby tires encrusted with mud.

Bela Karolyi steers toward a sparkling body of water just beyond the trees and launches into a story about how he dug the lake himself, learning to drive a bulldozer and pushing dirt for six months.

“I’m good at it,” he says. “I love it.”

Every bit the gentleman rancher in khaki pants and a red-checked shirt, Bela stops at the shore. Catfish — fat and black, as long as a man’s arm — gather near the surface to gobble chunks of homemade sausage he feeds them as treats.

“Hey, guys,” he says. “Big suckers.”

Much of the world remembers this man as the Romanian gymnastics coach who guided Nadia Comaneci to a perfect 10 at the 1976 Montreal Olympics. After his defection to the U.S., he molded a new generation of American stars that included Mary Lou Retton, Kim Zmeskal and Kerri Strug.

His voice remains strong, his words still full of gravel, but age has turned that bushy mustache to white. In recent years, Bela has traded Olympic glory for another sort of passion.

“We’re in the boonies,” he says gleefully. “The middle of Mother Nature.”

--

Down by the front gate, a large, blockish building stands out amid the pines. This is where Martha Karolyi — the other half of the famed coaching duo — spends her days.

Beneath the shine of electric lights. Insulated from the wilderness by a steady blast of air conditioning.

“I’m a city girl,” she says.

The life her husband has fashioned for them as they enter their 70s still prompts an occasional frown. She sees him checking miles of fence each morning to be sure his beloved red deer — he breeds them — remain safe from coyotes. She listens to his plans for adding another cabin or barn to a patchwork complex on 2,000 acres.

“We used to have a big house in Houston,” she says. “In a nice subdivision.”

The cavernous gymnasium is her refuge. It gives Martha a chance to keep nurturing girls and young women who travel miles of country road to learn from a legend.

On this day, dozens of the top females in the nation — including Gabby Douglas and Kyla Ross, both from the gold-medal U.S. team in the 2012 London Olympics — have arrived for training camp. The Americans are preparing for a string of major competitions including the P&G Gymnastics Championships, which start Thursday in Pittsburgh.

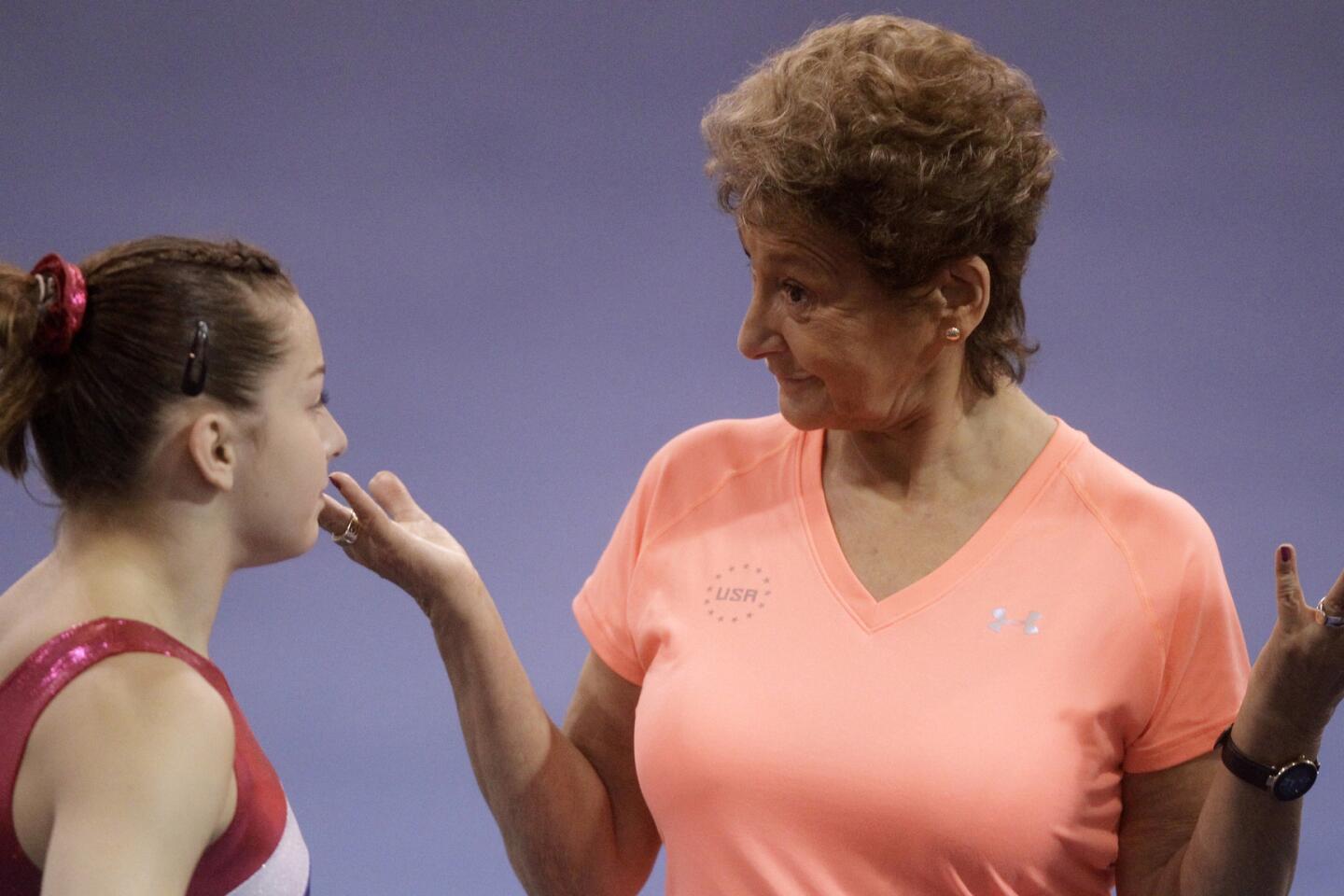

They know to begin practice by arranging themselves according to height. Martha walks down the line, inspecting their posture.

“Make sure the shoulders are not stiff,” she barks.

Three decades have passed since the Karolyis grew weary of the Communist-run sports machine, and slipped away from the Romanian team in New York City to request asylum.

Though they faced a wide-open future, Martha could not have imagined ending up in a place like this.

--

Their life in America began in 1982 when acquaintances provided the financial backing to open a gym in Houston. Retton became the first big star, followed by half a dozen others.

Moving to Texas gave Bela an opportunity to pursue his love of the outdoors and someone suggested that he try hunting in the Sam Houston National Forest.

On a typically humid Gulf day, he and some friends got lost tracking deer. They wandered out of the trees to a trail where a man drove by in a horse-drawn carriage.

“An old guy,” Bela says. “We became very good friends.”

In the months that followed, Bela’s new acquaintance showed him around the forest. They passed tattered fences that bordered private plots long since abandoned. It took some rummaging through records at the county courthouse to locate the owners.

“You could buy the properties cheap,” Bela says. “I find one and another and another.”

His holdings grew to 14 parcels scattered over many miles. Suspecting that federal authorities weren’t pleased about private land interrupting their vast public reserve, he proposed a swap.

The government agreed, he says, giving him all that contiguous acreage near New Waverly, a town about 60 miles north of Houston. Bela recalls: “I wanted a retreat for me and my family.”

--

First came the house.

Bela transformed a log cabin into something his wife might like with an updated kitchen and a place for grandchildren to sleep. A new family room proved troublesome as the roof kept collapsing.

“I never built anything before,” he says. “I make a lot of mistakes.”

Basic remodeling wasn’t enough for Martha. She wanted more.

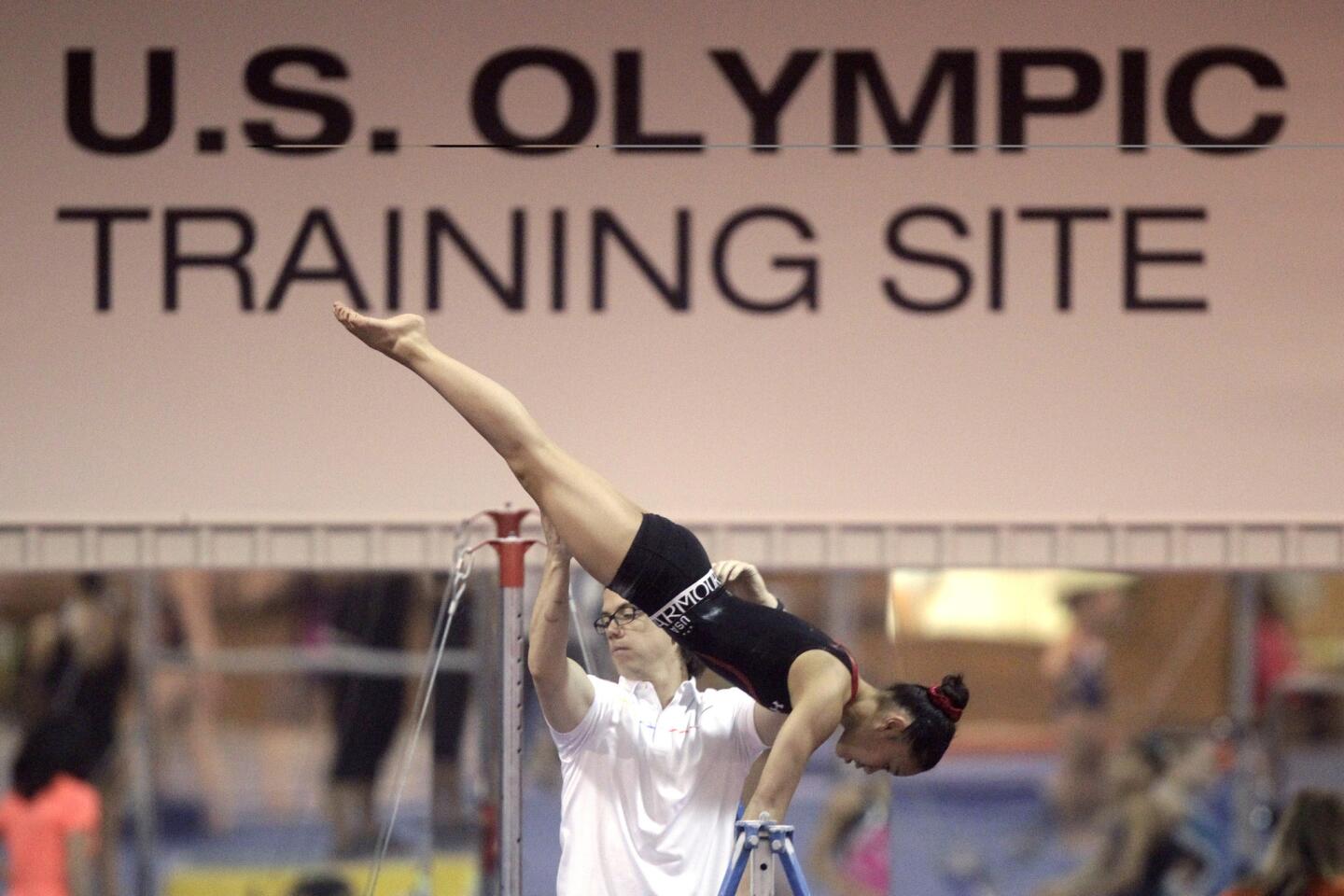

An old barn was converted into the gymnasium; with subsequent additions, it grew as large as an aircraft hangar filled with padded floors, balance beams and uneven bars.

The couple began holding camps there in 1984, gradually shifting their business from Houston, but more than a decade passed before Martha agreed to close the city gym and move to the country. In 1999, with the American team struggling, USA Gymnastics named Bela the national program coordinator and made the ranch a focal point for training.

“As a gymnast, you hoped to be asked out there,” recalls Zmeskal, who now goes by her married name, Zmeskal-Burdette. “It was an honor.”

The Karolyis forged a system based loosely on the centralized Communist model. Athletes continued working with personal coaches but visited Texas for periodic guidance.

Some coaches resisted the change and some athletes bridled at the workload, claiming Bela pushed them to injury. After a year or so, he says, “I had to step out. They had to elect someone they trusted.”

That someone was Martha, whose style was, as she puts it, “a little more diplomatic.”

The couple had reached equilibrium: Martha could remain devoted to gymnastics, showing up for practices with manicured nails and coiffed hair, while her husband could spend his time outdoors with hammers and bulldozers.

Talking about the ranch, Bela feigns weariness — “Always there is work” — but soon grows excited, his voice rising.

“Look over here,” he says. “I’m planting trees.”

Cabins with rustic wood siding dot the property, as do dorms that resemble roadside motels. Bela builds almost everything himself, enlisting the help of neighbors.

Beside the lake stands a lodge decorated with overstuffed couches, a billiard table and trophies — the heads of elk, impala, gnu and Cape buffalo — from his many expeditions. He says: “This is where I’m cooking hunting stews. My specialty.”

At one point, he cleared space for two large fields and opened a soccer camp. When the first group arrived, boys crawled atop hay bales in his new barn to sneak cigarettes and accidentally started a fire.

The grass on those fields now grows tall, serving as a pasture for Bela’s horses, miniature donkeys and camels.

“No more soccer players,” he says.

--

A smack reverberates through the gym as the reigning all-around world champion, Simone Biles, sticks a dismount off the uneven bars. Martha pauses from her incessant circling to suggest the routine needs more energy.

When Douglas springs off a vault and lands awkwardly on her back, the coach tells her: “Precise and clean.”

Though Bela often stops by the gym — he visits with campers and serves as a confidant in national team matters — there is so much else for him to do.

Peacocks run screeching across the property in the late afternoon while guinea fowl wobble about, picking bugs from the ground. Llamas find shade under a tree.

Turkeys, pigeons and rabbits live beside a lush vegetable garden. The dog pens near the house hold German shorthaired pointers, cocker spaniels, Hungarian Pulik and a wirehaired dachshund.

“Look at the baby,” Bela coos, calling to an unsteady kid among his goat herd. “Tell me what’s the problem.”

Back in the house, he entertains guests by cooking a pheasant he shot and pouring endless glasses of palinka, which he calls “Hungarian moonshine.”

The clear liqueur is made by slipping an empty bottle over a fruit tree branch and waiting for the bud — a pear, in this case — to grow inside. Next comes the fermentation process, the result tasting something like gasoline.

“Good,” Bela says. “Right?”

Another project has sprung up in his head. The next morning, he announces his intention to expand the dining hall, moving the walls to accommodate more tables and chairs.

When Martha hears this, she winces. How long can he possibly keep tinkering with this ranch of his?

“Hoo,” he says, grinning again. “Forever.”

Twitter: @LATimesWharton

More to Read

Get our high school sports newsletter

Prep Rally is devoted to the SoCal high school sports experience, bringing you scores, stories and a behind-the-scenes look at what makes prep sports so popular.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.