The Fall From Spyglass Hill

- Share via

On a warm August afternoon in 1973, the summer before Mary Katherine Schmitz started sixth grade, her little brother Phillip drowned in the pool behind the family’s home in Corona del Mar’s exclusive Spyglass Hill.

The swimming pool, lined with turquoise tiles and architecturally sited to take full advantage of the backyard’s panoramic ocean view, had just been filled. Former congressman John G. Schmitz was away on business, and his wife, Mary, busy with church work and her own campaign to defeat the Equal Rights Amendment, was counting on her eldest daughter once more to look after the child everyone in the family still called “the baby.”

The baby was a fearless 3-year-old, and when he took off his life jacket and stepped into the deep end of the pool, not even the diligent Mary Katherine--playing in the shallow end with her older brother Jerry--noticed the tiny splash. Only after their mother began looking for Phillip was he found, lifeless on the bottom of the pool.

Twenty-five years later, Mary Kay Schmitz Letourneau, married with four young children, went to a Washington state prison for the rape of a 13-year-old boy. Unrepentant, Letourneau insists she fell in love with the boy when he was a student in her sixth-grade class. They have a baby girl together--her fifth child--and now Letourneau is pregnant with their second child.

For the Schmitz family and other Mary Kay supporters, the best explanation for her stunning behavior may begin with what happened that warm summer day on the scenic hill in Corona del Mar.

“There is no question that her brother’s death, combined with other traumas Mary Kay suffered later, contributed to the tragedy of her life today,” says Dr. Julia Moore, the psychiatrist who evaluated the once-beloved Seattle teacher and diagnosed manic depression before she was jailed as a sex offender last November.

The story of the petite blond woman known at the Washington State Corrections Center for Women as prisoner 769014 is as sad as it is outrageous. And it mirrors, many say, the downfall of her father--the brilliant and flamboyant ultra-conservative Orange County politician who lost his career and, for a time, his family, when it was revealed that Southern California’s most outspoken advocate of family values himself had a mistress, also a former student, and two illegitimate children.

The Outspoken Congressman

In 1962, the year Mary Katherine was born, John George Schmitz was a Marine officer teaching other officers at El Toro about the dangers of communism. He made his first headlines that year for stopping a man who was stabbing a woman by the roadside near the Marine Corps base. With nothing more than the sheer authority of his voice, Schmitz disarmed the assailant.

Although the woman died, Schmitz’s reputation as a hero was made, and the next time his picture was on the front page, it was as the area’s newest state senator.

By then, Schmitz had attracted the support of such wealthy conservatives as hamburger magnate Carl Karcher, sporting goods heir Willard Voit and San Juan Capistrano rancher Tom Rogers. When congressman James B. Utt of Tustin died and Orange County Republicans needed a man to fill his seat in Washington, Schmitz, then a national director of the John Birch Society, retired Marine colonel and community college teacher, was the easy choice.

With such slogans as “When you’re out of Schmitz, you’re out of gear,” the unpretentious Wisconsin native who grew up scrubbing beer vats won the election and moved his family to Washington, when Mary Kay, the fourth of seven children, was 9. He quickly established himself as one of Congress’ most right-wing and outspoken members--and just as quickly enraged his most famous constituent, part-time San Clemente resident President Nixon.

Of Nixon’s historic visit to China, Schmitz, whose political hero was Joe McCarthy, quipped, “I have no objection to President Nixon going to China. I just object to his coming back.” His fellow Birchers laughed, but the president and his men were not amused. By the time election day rolled around, neither was Schmitz, who lost his seat to a more moderate candidate.

But that was not the end of Schmitz’s political career. In 1972, with George Wallace still ailing from injuries suffered in an assassination attempt, Schmitz took his place as the American Party’s candidate for president. He collected more than a million votes, but lost much of his longtime Orange County support.

“He was operating on a higher level of politics than any of us had the guts for,” recalls former Schmitz campaign treasurer Tom Rogers. “His philosophy was unbending, even for his fellow Republicans, and he never doubted his own abilities and was never humble . . . until it was too late.”

By 1982, Schmitz’s caustic remarks about Jews (“Jews are like everybody else, only more so”), Latinos (“I may not be Hispanic, but I’m close. I’m Catholic with a mustache”) and blacks (“Martin Luther King is a notorious liar”) had grown so outrageous that even the Birch Society dumped him. But what ultimately humbled him was the revelation that same year that Schmitz had a secret life that included a pregnant mistress and a 15-month-old son.

“It was an unimaginable shock. It was simply unbelievable,” recalls Santa Ana lobbyist and former Schmitz aide Randy Smith. What did not surprise Schmitz supporters, however, was his willingness to, as one put it, “stand up and take it like a man.”

When Schmitz’s mistress--a 43-year-old German immigrant, was charged with neglecting her son, Schmitz stepped forward to defend her and to identify himself as the father.

Although the neglect case was dropped, the damage to her lover’s family values-based political career had been done.

In court documents and interviews at the time, it was clear that Schmitz’s affair had begun in 1973, around the time his son Phillip drowned.

Democrats gloated. So did the many Republicans who felt they’d been tarred by Schmitz’s racially insensitive remarks and holier-than-thou political pronouncements. But, as they had done after Phillip died, the six remaining Schmitz children closed ranks around their parents. Again, they gathered together for hours in the living room, candles burning on the mantel, heads bowed in prayer.

“John or Mary led them in prayers as always, but this time, John tried to get Mary to use her religion to understand what had happened and to forgive him,” recalls one family friend. All the children were confused and angry, but none was more crushed than Mary Katherine.

A sweet-tempered, well-liked girl, she was a happy-go-lucky student and cheerleader who loved dancing and boys.

“Maybe her reputation was a little racy, but she was so gorgeous and so much fun, she was never, ever without a boyfriend,” recalls one former classmate.

At home, Mary Katherine was also a favorite. Her father called her “Cake.”

“She was the most beautiful of the children and by far the most devoted to John,” says former Schmitz aide Smith. “She was the one who sat beaming--like Nancy Reagan gazing at Ronnie--whenever her father spoke. She’d sit for hours after school in his office watching him work, helping stuff envelopes, whatever, anything to be near him.”

But when she found out her father had been having an affair with a woman who had once been a student in his government class at Rancho Santiago College, “Cake” felt as betrayed as her mother did, according to her classmate and others who knew her then.

Schmitz’s wife, Mary, a gifted and articulate defender of the so-called “anti-feminist” position, had given up a promising career as a chemist--she built Miller Brewery’s first test lab for Miller Lite--when she met John at a Marquette University graduation party in the 1950s.

The two had been married almost 30 years when the scandal of John’s affair ended his political career, but Mary, true to the teachings of her church, decided not to let it end her marriage. Too angry and humiliated to stay in Orange County, she took the advice of her good friend, astrologer Jeane Dixon, and moved back to Washington with her three youngest children. There, she joined Dixon’s real estate company and made a modest fortune selling high-priced homes in high-profile locales such as the Watergate complex.

Mary Katherine went off to finish college at Arizona State University but before graduating fell in love with a big blond football player, Steve Letourneau. When they found out she was pregnant, they married and later moved to Seattle.

The Woman in the Orange Jumpsuit

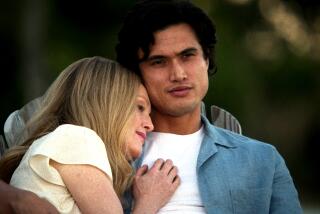

Reed-thin in her oversized orange prison jumpsuit, Mary Kay Letourneau is frail but as bubbly as the cheerleader she once was as she walks out to meet her attorney during one of his recent visits at the Washington Corrections Center for Women in the middle of Gig Harbor near Tacoma.

“She has so few visitors these days, she’s always happy to see a familiar face,” says her attorney and former neighbor, David Gehrke.

Those who have held the phone and peered through the thick plexiglass window say she talks nonstop about the baby--Audrey, whom she named after her mother’s sister and who will soon celebrate her first birthday--and the new baby who will be born this fall, the baby she says was conceived in the back of her silver Volkswagen Fox during the few months she was out of jail earlier this year.

It is this latest pregnancy that caused Judge Linda Lau to revoke the suspended sentence she had given her and send her back to prison for the remaining 7 1/2 years of her jail term.

Since her return to prison, she has become the darling of the afternoon talk show circuit and every supermarket tabloid’s favorite “exclusive” interview.

“You know, we have been lovers before, my darling and I, and we had at least 10 children together,” she told an interviewer for Mirabella magazine who told her he wanted to write a screenplay about Letourneau’s “forbidden love.”

“Someday, we will marry. We will all live happily together, and my two families will be one, and everything will be just perfect!” she told an interviewer for a local Seattle television station. “I couldn’t be happier. I have a new life inside me. It’s a sign, a sign that God wants us to be together, to be one.”

Her “consistently upbeat view of life today,” says Gehrke, is tempered only by her sorrow that “all this had to come out” during her father’s life.

Psychiatrist Moore told the weekly public radio program “The Infinite Mind” that the Letourneau marriage was “on the rocks when Mary Kay went into her depression over her father’s illness.” According to Moore, Letourneau was convinced that her father, who has cancer, was dying.

John Schmitz, who until his daughter’s legal troubles became public worked part time at a political memorabilia shop in Washington’s Union Station, now spends most of his time in Virginia at a vineyard his other children bought him a few years ago. Through friends and family members, Schmitz declined The Times’ repeated requests for interviews.

“This is a strong family, and they’ve been through crises before, and it has only made them stronger, but this is a real test,” says friend Voit.

Although the family has committed itself to helping pay for the educations of the four Letourneau children, it had not contributed any money to her defense until a recent commitment to assist with any appeal.

The Questions About Her Mental State

‘I have found true love at last,” Mary Kay told a reporter for a tabloid TV show. But why, she asked, suddenly angry, “Why are all these people using me to start digging up all those horrible things about my father’s past? It’s a conspiracy! My father has a right to die with dignity.”

“When people hear that Mary Kay is pregnant again,” says Gehrke, “that she is pregnant by the same boy she was sent to prison for raping, they say to me, ‘How could anybody in their right mind do such a thing?’ And I say, ‘That is the point exactly. Clearly, Mary Kay Letourneau is not in her right mind at all.’ ”

And the proof of that, says Letourneau psychiatrist Julia Moore, is that when Mary Kay took the medications prescribed to control manic-depressive illness (also known as bipolar disorder), “she returned to her senses.”

“This is a neurobiological illness. And her symptoms are classic: She barely sleeps, her thoughts go a hundred miles a minute, she needs different pieces of paper to arrange her thoughts when she’s talking, she’s distractible, and in her hypersexual state, she takes enormous risks. Like having sex with a sixth-grader.

“For a patient like this,” says Moore, “morality is going to begin with a pill.” Moore and other members of Letourneau’s defense team believe that any number of traumas may have set off her mental illness.

Gehrke appealed for leniency during November’s televised hearing of charges against Letourneau, arguing that his client had been emotionally and physically abused by her husband.

“In two of the three cases,” said Gehrke, “she went to the hospital for treatment, and police were called.” Although no criminal charges were filed, the allegations are repeated in documents filed in the Letourneaus’ divorce case.

Steve Letourneau, an Alaska Airlines supervisor who is reportedly writing a book about his relationship with Mary Kay, has not commented publicly on the charges. A few months after he discovered love letters from his wife to her former student--but while she was still living at home with him and their children, ages 4 to 13--he met an Alaska Airlines flight attendant while vacationing in Puerto Vallarta and in August moved her into the home he now shares with his children in Anchorage.

Though barred by the court from seeing her children, Mary Kay has tried to stay in touch with them. Her daughter Audrey is being raised by her young lover’s mother, who is expected to take in the new baby as well.

Two of her three older brothers, along with her two younger sisters, took Mary Kay’s four Letourneau children into their homes for last summer.

John Patrick Schmitz, a much-admired White House counsel during the Bush administration, now has a successful law practice in Washington and Berlin. Joseph Schmitz, who attended the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis, recently left the service to join another high-profile law firm in the nation’s capital.

Jerry, who is two years older than Mary Kay, is an engineer who works in Arizona and Nevada. When he was 23 and working as a staff member of the San Francisco Scientology mission, his parents threatened to sue the Church of Scientology for alienating him from his family and the Catholic Church.

Her younger sisters Theresa and Elizabeth are both homemakers who live in the Washington, D.C., area.

None of her siblings have commented publicly on their sister’s legal troubles.

In Mary Kay’s parents’ Washington home, a big red brick house behind the Supreme Court building on Capitol Hill--the house once owned by John Schmitz’s idol Joe McCarthy--the extended Schmitz family gathers now as they did years ago on Spyglass Hill to face head-on the latest crisis.

But this time, it is not their father, but the daughter who so adored him who needs their help and support.

“This is a family that does not run away from its problems, that does not look for excuses but that does what has to be done for whomever needs their help,” says Michael Horowitz, a former Reagan administration counsel and close friend of John Patrick Schmitz.

For the time being, the family, which is bringing in a new attorney to prepare an appeal for Mary Kay, isn’t eager to rush in to save the day. Nor is her father rushing to her rescue. Although he is well enough to travel to Wisconsin for family celebrations, he apparently has made no trips to Seattle to see his eldest daughter.

*

Los Angeles Times librarian Sheila A. Kern contributed to this story.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.